Our dojo history sprouts from two indigenous roots, Korean Chang Moo Kwan and Japanese Tomiki Aikido, and Catawba Valley Martial Arts has direct connections to the patriarchs of each of these traditional arts, as a grandson retains from his grandfather.

Much of this dojo history was borrowed from From Point Zero to Ground Zero: An Excavation of Twelve Indigenous Chang Moo Kwan Forms 1 , a thesis submitted by Sensei Jesse Boyd in partial fulfillment of the requirements for black belt rank in the traditional art of Chang Moo Kwan under the authority of Grandmaster Nam Suk Lee's last students. Sensei Boyd received his black belt in Chang Moo Kwan on April 17, 2015 in San Pedro, California following the submission of this thesis and a grueling physical test that involved one of his Cheonjikido students as the uke.

contents

“A successful martial artist must know where he came from to know where he is going; and if one values the lessons of history, his art is by default eclectic, pragmatic, and evolving—not away from the roots but through them. Those that don’t know their history are doomed to repeat it; those that don’t know their history may be doomed NOT to repeat it.”

the chang moo kwan root

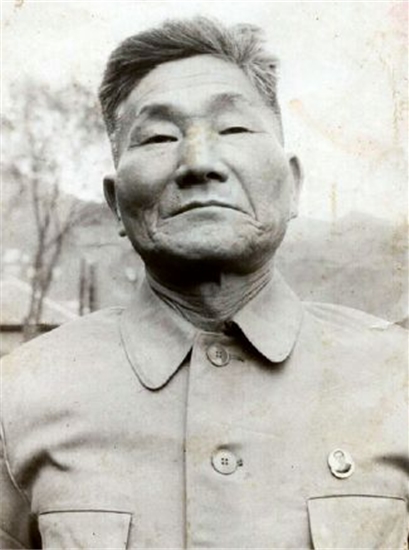

byung-in yoon

The story begins long ago in Manchuria. This branch of our lineage can be traced back to when a government employee appointed at the end of the Korean Yi Dynasty (1392-1910) was pushed out of his position by Imperial Japan’s 1909 invasion of the Korean Peninsula. To avoid trouble with the Japanese forces, Young-hyun Yoon took his family, including three sons, and fled to Manchuria.

2

There, the family fell into financial hardship, so the eldest son, Myoung-keun Yoon, worked hard and eventually secured ownership of a local distillery. Later, it was Myoung-keun that brought the family out of poverty, and he eventually fathered three sons himself, the middle child being Byung-in Yoon who was born on May 18, 1920.

3

While attending elementary school, Byung-in Yoon became fascinated with ChineseChuan-fa4 as he watched it practiced in a nearby dojang and asked the instructor, a Mongolian Grandmaster, if he could join the class. 5 “The instructor firmly refused, for in China, the teachings of martial arts were for Chinese natives only and kept secret from all outsiders.” 6 Grandmaster Kim Pyung Soo 7 once relayed a story that he heard from three independent witnesses at three different times in his life; and all three of these witnesses personally knew and trained with Byung at some point prior to the Korean War:

Byung In Yoon could not stay away from the school. During the day, he would jump up and down in front of the school's windows glimpsing what he could of classes. The instructor would catch him and sent [sic.] him away from the school. Determined to somehow be a part of the school, Byung In Yoon returned. This time he cleaned the area around the dojang and in front of the dojang entrance where the shoes of the instructor and all of the students lay. He meticulously arranged the shoes in neat, orderly rows. He returned every day to this task. The instructor came out of the dojang surprised to find this orderly and well kept area, day after day. He noticed that someone had also rearranged his shoes so that the toes pointed away from the entrance, ready for him to easily slip into and walk away. He was very intrigued and tried to find the student who was so dedicated. He found that it was not his students, but the little Korean boy who was determined to show his sincerity. The instructor was so impressed with Byung In Yoon's tenacity and sincerity that he made an exception and allowed him to join the school. Never before had a Korean national been accepted to learn the Chinese martial art of Chu'an Fa. 8 Byung-in Yoon studied Chuan-fa from the Mongolian until he graduated from high school and was sent by his family to study at Nihon University in Japan. One of his cousins, Byung-bu Yoon, who grew up with him in Manchuria, described Byung as “very bright, sincere, quiet, always helping people. Typical martial artist.” 9 Moreover, “He was very strong. If he ever had to fight, he would never seriously hurt anyone. He just did enough to make them stop.” 10

During his childhood, while studying Chuan-fa, another story has been passed down concerning a severe injury that Byung suffered to his right hand. During a cold Manchurian winter, when the Siberian winds typically blow down from the North, Byung was huddled around a neighborhood fire with some friends and was shoved forward as a joke into the flames. To prevent his body from being burned, he planted his right hand into the hot coals and leapt up to safety. No one was around to help, so he ended up losing the ends of his fingers. To hide this injury, Byung-in Yoon would wear white gloves in public and while teaching martial arts classes. Later, some of his students would wear white gloves as a respectful tribute to their teacher. 11

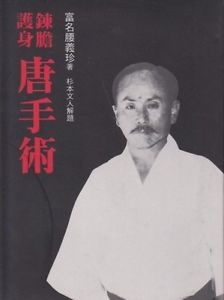

Byung-in Yoon must have been a good academic student, for he was the middle son, and usually it was the eldest who received preferential treatment in Asian culture and was sent out to study abroad. At Nihon University in Tokyo, he majored in Colonial Agriculture from 1939-1941 and had the privilege of meeting and training with Kanken Toyama (1888-1966) of Okinawan karate lore, a faculty member at the university at that time and the sensei for the university karate club. Toyama had studied the Shuri-te karate tradition under Anko Itosu12 for eighteen years and was appointed the title of shihandai (i.e. assistant master) to Itosu in 1907 at the Okinawa Teacher’s College. Also, Toyama and Gichin Funakoshi were the only two students to ever be granted the title of shihanshi (i.e. protege) by Itosu.13 Anyway, Toyama also received supplemental instruction from Kanryo Higaonna (1853-1915), the founder of the Naha-te karate tradition. Around 1924, Toyama moved his family to Taiwan; and there, he studied Chinese Chuan-fa for seven years. In 1930, he relocated to Tokyo and opened his first dojo, calling it Shudokan. There, he simply taught an eclectic blend of what he had learned from Itosu, Higaonna, and Chuan-fa. Toyama never claimed to have originated a new style of karate, and like Funakoshi, he never referred to his system by the name of his dojo.

How Byung-in Yoon actually met Toyama is quite interesting; and the circumstances surrounding this happenstance encounter clearly indicate how a spirit of cheonjikido pervaded the Korean’s martial arts training and teaching from early on. While studying at Nihon University, Byung was often seen during lunch using a large tree as a makiwara post, punching and kicking it day after day until the tree itself started to lean.14 While Byung pretty much kept to himself, some of his Korean friends joined the university karate club supervised by Kanken Toyama. After some time, one of the Korean students started missing practices at the club so he could spend more time with his girlfriend. This, of course, angered the Japanese students who considered it a great privilege for the Koreans to be included in the class. There was already racial tension on the campus, and Japanese gangs would often tussle with Korean gangs. Fueled by this, the Japanese karate club students pursued the slacker and beat him up pretty badly. The Korean victim knew about Byung and his Chuan-fa and had often seen him outside practicing in the courtyard. He begged Byung to help him: “You are Korean, I am Korean, will you please help me?”15 Byung-in Yoon agreed, and at the next scheduled beatdown, he showed up on the scene and quickly sprang into action using the graceful Chinese Chuan-fa he had learned growing up in Manchuria. He skillfully deflected and evaded the Japanese karate students’ strikes and kicks and fought off many attackers simultaneously, so much so that the Japanese attackers gave up and ran back to tell their teacher about what had transpired. Toyama, revealing his character, responded in a way completely foreign to the typical egocentric martial arts instructor of today. He actually invited Byung-in Yoon to sit down with him and explain about “the skillful non-karate martial art he had used against his students.”16 He shared with Toyama about studying Chuan-fa in Manchuria; and Anko Itosu’s shihandai immediately appreciated this background, for he, too, had studied Chuan-fa in Taiwan for seven years. The two immediately decided to exchange knowledge: Byung agreed to teach and refresh Kanken Toyama in the art of Chuan-fa if the karate master would teach him Shudokan Karate. Byung’s skill level was so advanced that Toyama soon awarded him the rank of Yondan and made him captain of the university karate club. Toyama held the rank of Godan at that time, so this made Byung his highest ranking student. Such a promotion was truly special; it would have been a rare blessing for a Japanese student and even more unheard of for a Korean national. Under Toyama, Byung would have certainly learned the secrets of the five Heian/Pinan kata as well as Naihanchi and Kushanku.17

On August 15, 1945, the Japanese surrendered to the Allies, thus marking the end of World War II and the end of the 36-year occupation of Korea. Finally, Byung-in Yoon could return to the home of his fathers. He followed two of his Korean friends from the Nihon University karate club to the Chung-yang Rhee neighborhood of Seoul. One of these friends invited Byung to help teach an eclectic mixture of Chuan-fa and karate at the Cho-Sun Yun Moo Kwan judo school, which he did for six months. Then, he was invited to start a class at the Cho-Sun Central YMCA in Seoul sometime in 1946 at a time when martial artists were used as unofficial law enforcement deputies to help insure safety on the streets of the post-WWII Korean capital. It’s interesting that in one of Kanken Toyama’s instructor directories, published sometime in 1946 or 1947, Byung-in Yoon is listed as the “Chief Instructor at the Cho-Sun YMCA” with the rank of 4th dan.18

At the Seoul YMCA, Yoon originally labeled his style Kwon Bop Kong Soo Do, a Korean phrase that literally translates: “the way of fist law AND empty hand.” This designation not only pays tribute to the spirit of eclecticism that he wove into his art from its outset, but in its literary form, one can see his conviction that a superior martial style reflects a proper blending of hard art (i.e. fist law) with soft art (i.e. empty hand), certainly an outflow of his training background. Later, Byung would suggest that the style be called Chang Moo Kwan (said change would establish itself more fully under Byung’s protege, Nam Suk Lee), and in early years, the curriculum was complex and the training was severe. “In the beginning, there were 500 members, but three months later, there were only 180 left.”19 Byung’s style reportedly consisted of a unique blend of Shudokan karate and northern Chuan-fa. The techniques were said to have a smooth yet hard appearance when practiced or demonstrated.20 Supposedly, practitioners were required to perform several Chuan-fa forms, including Dan Kwon, Doju San, Jang Kwon, Taijo Kwon, and Palgi Kwon, as well as at least two staff forms, one created by Byung himself and another brought over from Shudokan.21

Sometime before 1950, Byung was appointed faculty at both Sung-Kyun Kwan University and Kyoung-Nong Agricultural College and taught his unique blend of Chuan-fa and karate at both places.22 He was also offered a job as a bodyguard for Korean President Syngmahn Rhee but turned it down. Supposedly, he wasn’t able to properly salute the President because of the maimed fingers on his right hand from the aforementioned childhood injury, and he wanted to avoid that embarrassment.23 With many new responsibilities, Byung appointed Nam Suk Lee, one of his top students, as the primary instructor at the Cho-Sun YMCA.

In June of 1950, with the onset of the Korean War, many dojos were thrown into turmoil as students and teachers alike were called up to duty. During the conflict, Byung-in Yoon went missing; and for many years, he was thought to have perished. In 2005, however, some information was recovered concerning Byung’s family by Kim Pyung Soo, an original student of Byung and Lee and a notable personality in terms of preserving Byung’s influence in Chang Moo Kwan forms and self-defense technique. Apparently, Byung was lured under duress to North Korea in 1950 by his elder brother, a Captain in the Communist North Korean Army who showed up unexpectedly and demanded that his brother accompany him north. On November 25, 1951, as a result of peace talks between North Korea and the United Nations, the Korean Peninsula was officially divided at the 38th parallel: North Korea would control the north part of the peninsula (with Soviet Union occupation) and South Korea would control the south (with U.S. occupation). During this time, Byung-in Yoon showed up in a POW camp on Gojae-do Island. As part of a prisoner exchange agreement between the North and the South, POWs were given the option to decide where they wanted to go. Byung opted to return south, but as he was being escorted off the prison grounds, North Korean POW soldiers supposedly attacked him and prevented him from leaving. The option to go back home was lost, and as a result, Byung’s activities are completely unknown from this time until 1966. His Chang Moo Kwan students lost all contact with him. From 1966 to mid-1967, Byung may have taught Gyuck Sul (i.e. “special combat strategy”, an eclectic art) to North Korean special forces under compulsion, possibly as a prisoner of war. In 1967, he was reportedly told that Gyuck Sul could not be taught as an international sport and was then sent to work in a concrete factory in the North Korean city of Cheonjin, where he allegedly died of lung cancer in 1983.24

The Cho-Sun YMCA in Seoul was completely destroyed by bombs from U.S. warplanes sometime in late 1950 or early 1951. Moreover, Chang Moo Kwan instructors were scattered across the Korean peninsula training military personnel until the armistice. After the recovery of the capital by allied forces, surviving teachers started trickling back into Seoul, and training resumed at an integrated government office under Nam Suk Lee in 1953. An extensive effort was made to find Byung-in Yoon, but the search turned up empty. A body was never found, and he was declared legally dead. On October 5, 1953, Nam Suk Lee was appointed president over Byung’s style and immediately oversaw the training of 500 students and 600 government employees.25 At this time, Lee formally adopted the designation Chang Moo Kwan (lit. “building a martial arts house”) as the official style name, maintaining that “Master Yoon was considering this name prior to his disappearance.”26

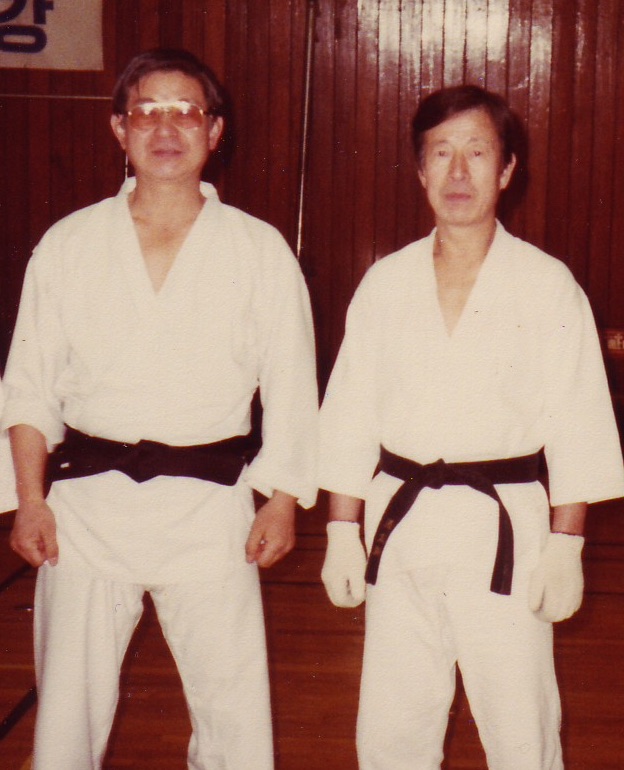

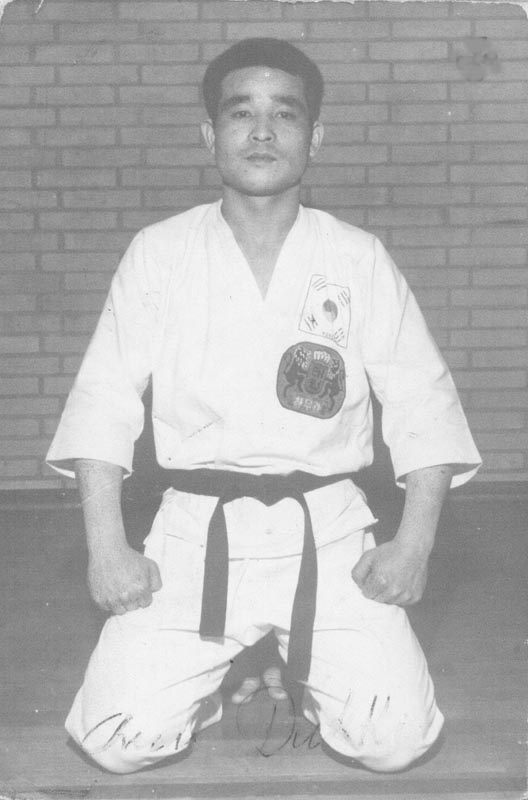

nam suk lee

Nam Suk Lee was born on June 28, 1925 in Yeo Joo, about forty miles south of Seoul. In the 1930’s and during the Japanese imperialist occupation of the Korean Peninsula, his family moved to Seoul. Early on, a young Lee showed great initiative and leadership qualities in sport and academic activity. As a teenager, while sauntering down the street, he happened to stumble upon a tattered and discarded Chinese translation of of Gichin Funakoshi’s Karate Jutsu lying in the gutter. He took it home and began to pour over the text and accompanying black and white photographs. Of course, this perusal would have included in-depth breakdowns of the five Heian/Pinan kata, Kanku-dai, Naihanchi, and others. Interestingly, footprints of all seven of these traditional Okinawan forms are seen in The Twelve. Nam Suk Lee was hooked, and for him, finding that book was “point zero.”27

During this time: “If teenage Nam Suk Lee would have been discovered training by the unforgiving Japanese soldiers, death could have been the penalty.”28Undaunted by the danger and hungry for knowledge, Lee gathered others to himself and secretly practiced with them what he had gleaned from Funakoshi’s text. Sometimes, they would train at the school playground, or hiding behind a wall, or wherever they could be outside the gaze of the Japanese military police. In a personal interview with Grandmaster Jon Wiedenmen shortly before his death in 2000, Lee recalled many of the trials and tribulations of training during this time, one of which included secretly removing roof tiles from local buildings and breaking them with kicks and punches.29

In 1946, after WWII and the liberation of the Korean Peninsula from the Japanese Imperialists, Byung-in Yoon started his school at the Cho-Sun YMCA. Nam Suk Lee was one of the first students, and despite having “no formal martial arts training when he met Byung,” Lee quickly became the dojo’s top student.30 Unlike the 65% of the original 500 Cho-Sun YMCA members who went AWOL, unable to handle the severity of the training, Lee stuck around and was given control of the YMCA dojo before 1950 as Byung’s responsibilities increased. And, by the age of 28, following the Korean War and Byung’s disappearance, he assumed control over all of his teacher’s schools, appointed October 5,1953 the second President of the Chang Moo Kwan, a name formally adopted by Lee though he maintained that it had been Byung-in Yoon’s idea.31 Quickly, Nam Suk Lee’s organizational skills in this new position became apparent and renowned. Soon, he had 500 students at the central dojo and was also teaching 600 government employees.32 And, he would ultimately be responsible for Chang Moo Kwan’s strong influence in the evolution of Korean Taekwondo.

On April 11, 1955, leaders and historians from nine of Korea’s kwans (i.e. martial arts houses or traditions), including Lee, met and agreed to unite under the banner of Taekwondo, a designation that had been submitted by General Hong Hi Choi. This name was approved because of its resemblance to Taekyon, a traditional Korean term that had been used to describe martial arts in military training, and because it described both hand and foot technique. Although a loose organization was formed under the banner of Taekwondo, it was agreed that dojos were to maintain their independence concerning martial arts philosophy and differences in technique. The prevailing notion was to prevent the loss of the unique expressions of each kwan. Notwithstanding, “Tae Kwon Do has been the recognized name for Korean martial arts ever since.”33 Following this agreement, Lee became busier in his efforts to solidify the assimilation; and by 1957, he was no longer actively teaching at the original Seoul dojo.

Though secondary in some ways to this discussion, a bit of a tangent is worthy of mention: Kim Pyung Soo, a Sandan and one of Lee’s original students who had also learned from Byung, was placed in charge of conducting the majority of classes.34 Soo wanted to continue learning beyond Sandan, but as highest active rank, he couldn’t find anyone from the other Chang Moo Kwan dojos with enough free time to instruct him. So, he taught at Lee’s old dojang and would take classes as a student at the nearby Kangduk Won.35 Another one of Nam Suk Lee’s assistant instructors discovered this and ordered Soo to choose one dojo or the other. Kim Pyung Soo chose to stay at the Kangduk Won dojo as a student. Because of his reputation as a teacher and martial artist, many of the early Chang Moo Kwan black belts followed him.36 In 1968, Soo immigrated to Houston, Texas where he continued to teach an art that more closely preserved forms and techniques from Byung-in Yoon’s Chang Moo Kwan, apart from the international sporting elements that have come to characterize Taekwondo.37 On December 18, 2005, Soo was able to arrange a meeting in Korea with Byung-in Yoon’s family. At this meeting, he learned many things about Byung’s childhood from his 2nd cousin and was shown a letter written by Byung from North Korea and dated April 4, 1974. It was these interviews that revealed what happened to Byung in 1951, details of his life from 1966-1974 discerned from the aforementioned letter, and the circumstances of his death in 1983.38 Interestingly, some of the pictures from this meeting, as well as images of the 1974 letter can actually be seen on the website for Kim Soo Karate.39

In 1961, Nam Suk Lee joined with other national martial arts leaders to form the Korean Taekwondo Association (KTD), a tangible result of the 1955 assimilation agreement. In 1967, he was appointed General Director of KTD, and in 1969 (and again in 1971), he would serve as Vice-President. Under Lee, Chang Moo Kwan grew to be the overwhelming influence in the evolution of Taekwondo, and it was viewed, for some time, as the leading self-defense method.

By 1973, the prevailing opinion was that Taekwondo needed to go international. Thus, the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF) was formed in South Korea with Nam Suk Lee appointed as one of the Executive Council Members. At this critical juncture, Taekwondo started moving away from its original image of an eclectic assimilation of unique kwan expressions and began to embrace an international sporting label as a result of the overwhelming influence of General Hong Hi Choi. Unquestionably, though, it was Lee’s leadership which cemented Chang Moo Kwan as the foundation of the WTF, and he dedicated much of his life to the spread of this tradition, rightfully remembered as the style Patriarch. The WTF eventually set up dojos all over the world. At it’s pinnacle in 1976, the influence of Chang Moo Kwan via the WTF was being taught in around 900 dojangs, almost half of which were outside of Korea.40

When everything went international, however, Lee soon found himself beset by administrative duties and less able to preserve the indigenous Chang Moo Kwan lineage and any of Byung’s influences. Not only was he entertaining visitors from all over the world, but he was forced to travels to many countries, including extensive time spent in the United States; and there was little time to train.41 In fact, by the time he popped up in San Pedro, California in 1997, it is said that he hadn’t instructed a class in nearly thirty years.42 Moreover, “he had not trained in a long time and had no uniform or belt.”43

In the mid-1980’s, Nam Suk Lee moved to San Pedro, California to be closer to his children; and at this time, for whatever reason, it appears that he was no longer involved in the World Taekwondo Federation or active in the pursuit or propagation of Chang Moo Kwan. Based upon things later taught and expressed when he came out of retirement, including his dying wish that indigenous Chang Moo Kwan be preserved outside of Taekwondo, it is a fair assumption that Lee became disgruntled with the politics, the competition, and the business side of martial arts: sad eventualities that inevitably lead to questionable ethics, the watering-down of technique, and divergence from indigenous tradition. By re-locating to relative obscurity in the United States, he essentially and understandably walked away.

Years would pass before Lee again donned a dobok44 and a belt. In 1997, he was convinced to come out of retirement by a group of local Chang Moo Kwan black belts who found him in San Pedro. There, in a YMCA, he spent the last years of his life resurrecting and sowing seeds to preserve indigenous Chang Moo Kwan fundamentals, forms practiced in the original Seoul dojo, and the overriding principle of “cultivating capabilities.” This motto which appears on the official San Pedro Chang Moo Kwan patches today is undoubtedly a subtle tribute and reflection of the integrative spirit of chang moo kwan or cheonjikido originally sown by Byung-in Yoon in his primary protege.

Following a relatively routine surgery in August of 2000, a massive stroke killed Nam Suk Lee. Upon his death, Jon Wiedenman, as one of his last and highest ranking students, designated him Supreme Grandmaster and awarded him the rank of 10th Dan in Chang Moo Kwan. At the time, Sensei Jesse Boyd was a Nidan regularly teaching and training in North Carolina and occasionally pondering those two names at the top of his old student manual (Byung-in Yoon & Nam Suk Lee), names associated with the elusive style of Chang Moo Kwan. He often wished he could learn some of the old CMK katas and had absolutely no idea that Nam Suk Lee had spent his last days reviving them in San Pedro. Sheer profundity.

chang moo kwan in north carolina

Sometime during the 1960’s, before the formation of the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF), a dojang opened up in Salisbury, North Carolina under the leadership of Chun Duk Ki (1940-2001), a former Korean National Fighting Champion and a Salisbury police officer who had come to America to make a better life. Ki, at some point, had been a student of Duk Sun Son, renowned Taekwondo instructor via the Chung Do Kwan lineage; and he held the rank of 7th Dan in Taekwondo at the time. Interestingly, however, Chun Duk Ki’s Salisbury dojo was named Chang Moo Kwan Taekwondo, and the original dojo patch bore the hanja characters for Chang Moo Kwan as well as the typical style symbols: a pair of dragon horses, a fist, and a shield.

Little accessible information regarding Ki and this dojo remains, including specifics about his connection to indigenous Chang Moo Kwan. Sadly, the few of his original students still living in the area are no longer actively training, remain pretty tightlipped, and won’t share much. Notwithstanding, from everything I have gathered, the curriculum at the Salisbury Chang Moo Kwan was hardcore, a lot like the early days of the Seoul dojo. It involved much realistic free fighting with little to no protective gear; the importance of kata and bunkai application were emphasized; the sporting side of Taekwondo was disdained; and the techniques were said to have a smooth yet hard appearance, like what had been described concerning Byung-in Yoon’s early CMK teaching.45

Perhaps a clue as to Chung Duk Ki’s connection to Chang Moo Kwan and corresponding disdain for the big Taekwondo organizations can be seen in the mission statement of one of his original students who went on to train in other arts and presently resides in Catawba County, North Carolina, running a small dojo out of his home: “We . . . still train as the Masters before us trained. We do this because it is the natural way of things. This is the way the Masters intended it to be. The Martial Arts has to be a personal journey through training. We dance to our own music and answer to no one but ourselves. We are not an organization of control. We strive only to control our inner selves through training and life, nothing more and nothing less.”46

By the mid 1960’s, Chun Duk Ki began turning out his own Chang Moo Kwan black belts. Doug Bassinger and a man named Misenheimer were two of the first. By the late 1960’s, at least two more were added, Richard Yount and James Clements.47 Just before 1970, however, Chun Duk Ki moved to Canada.48 In fact, obituary records out of Edmonton, Alberta show that he died there on December 20, 2001 at the age of 61. Any doubts about Ki’s historic connection to Byung-in Yoon, Nam Suk Lee, and indigenous Chang Moo Kwan are removed by the fact that he actually shows up in Chang Moo Kwan’s 1976 Green Book Directory on the bottom-left of page 182, listed as a Chang Moo Kwan instructor in Canada.49

the southern karate association

Evidently, Master Ki’s relocation prompted Richard Yount to found the Southern Karate Association in 1970; and it’s aim was to water and grow the Chang Moo Kwan seeds that had already been sown in Salisbury. In the South, at that time, karate was used as a general and recognizable designation for all martial arts and had almost become the idiomatic English translation for many styles, including indigenous Korean arts, that wanted to distance themselves from the watered-down sporting and competition arenas. It is my understanding that Southern Karate Association (SKA) was little more than a name change for an eclectic art with direct ties to indigenous Chang Moo Kwan.

A subtle proof of this can be seen in a Statesville Record and Landmark newspaper ad for the annual Dogwood Festival, dated April 14, 1969. It lists “KARATE Exhibition by Chun-Duk-Ki on Courthouse Lawn 2:00 to 4:00 P.M.”50

Despite the long move, Chun Duk Ki continued to maintain ties with his North Carolina students.51 And, he oversaw Southern Karate Association promotions. In an old 1995 Carolina Karate Association Manual & Directory that Sensei Jesse Boyd has in his possession, four individuals who would later establish the CKA in 1975 are listed as having received their Shodan ranks (two in 1974, and two in 1975) from the Southern Karate Association with Chun Duk Ki as the head instructor.52 Obviously, Chang Moo Kwan endured in North Carolina through the Southern Karate Association.

carucado

Around 1975, for reasons unknown, the Southern Karate Association either ceased to exist or suffered from partition.53 Four of Richard Yount’s original students, who trained under the supervision of Chun Duk Ki, either broke away to form the Carolina Karate Association (CKA) or replaced the SKA with a new designation. Perhaps this had something to do with the difficulty of maintaining a long-distance relationship with Chun Duk Ki who was busy teaching Chang Moo Kwan up in Canada. Notwithstanding, on December 1, 1975, the Carolina Karate Association was formally established, and the style was officially renamed Carucado.54

The original Carucado Board of Directors consisted of Chairman Gary Godbey, who held the highest rank of the four, President Jerry Cope, Keith Allen, and Lee Presnell. It could be that this reorganization was also related to the mutual interest of these four individuals in the art of Aikido. It is my understanding that Godbey and Allen personally trained in a Catawba County Tomiki Aikido dojo in the 1970s. All four are listed in the aforementioned CKA Directory as having “previous training” in Aikido. Moreover, this manual defines Carucado as “an eclectic style” influenced by Aikido.55 Interestingly, at the end of said manual, two effective Aikido arts—Irimi-nage and Tenchi-nage—are listed as “Ki Applications” of Carucado kata technique. The circular motion and evasive kuzushi of Aikido is very similar to the old Northern Chuan-fa in terms of its self-defense principles, extension of ki, proper balance of power and fluidity, and redirection of force. I find it interesting that as Byung-in Yoon originally valued a proper balance of hard and soft art, so this same conviction endured thirty years later in North Carolina through a tradition undoubtedly tied to Chang Moo Kwan via the Green Book’s Chun Duk Ki. Like original Carucado kata, The Twelve taught in San Pedro, California by Nam Suk Lee are ripe with soft, circular, and evasive bunkai application, including Aikido’s irimi-nage and tenchi-nage.

In tracing the link between Chang Moo Kwan and Carucado, some additional statements from a 1995 Carolina Karate Association Manual & Directory are worthy of note. Under Organizational Purposes and Goals, it reads; “Allowing students to pursue Karate according to his or her own interests and abilities.” This is simply another way of saying what Nam Suk Lee summed up in two words when he succinctly defined Chang Moo Kwan: “cultivating capabilities.” Another one of these listed goals is “Emphasizing competition with one’s self rather than against others.” Later, under General Policy, the manual states: “Tournament participation is not required” and that all tournament practice (i.e. martial sport) is to be done “outside of regular class time.” This is the spirit of Chun Duk Ki and the aforementioned mission statement of one of his original students. Moreover, it indicates, at least on paper, that what Nam Suk Lee desired before his death—the preservation of Chang Moo Kwan outside the framework of international sporting competition—was transpiring, or an attempt was at least being made to that end, with the establishment of the Carolina Karate Association. One final statement from the Philosophy of the Carolina Karate Association Hierarchy in this manual is worthy of note: “Each instructor is the MASTER of his/her own school and students. It is not the business or intent of the Carolina Karate Association to become involved in the day to day teaching practices, priorities, or liabilities, of its instructors.” This open-mindedness, at least on paper, reflects the same spirit of open-mindedness to martial arts that Kanken Toyama amazingly showed toward Byung-in Yoon at Nihon University, an open-mindedness that was later undoubtedly shared between Byung and his students. By the 1980’s, the Carolina Karate Association had dojos at YMCA’s in Salisbury, Mocksville, Greensboro, and Catawba County, North Carolina.56

This tracing of our dojo history has thus brought us to the 1980's in Catawba County, North Carolina via direct descent from indigneous Korean Chang Moo Kwan as developed and disseminated by Grandmasters Byung-in Yoon and Nam Suk Lee. Now, let's turn to the other indigenous root of the art of Cheonjikido, a root with which we also assert direct descent from the founders.

the tomiki aikido root

daito-ryu jujutsu

The origins of aikido principle date back more than 1,100 years to Prince Teijun Fuiwara, the 6th son of Japan’s 56th Emperor Seiwa Fujiwara (850-880 AD). Teijun assembled the Genji-no Heiho, a group of warfare principles ranging from the construction of forts to strategy to principles of individual combat. With regard to the latter, these are generally acknowledged as the first Japanese grappling system.57 The Genji-no Heiho was inherited by Teijun's son, who was given the name Minamoto. It was then preserved as a secret family art through his descendants, the Seiwa Genji.58 In a mere four generations, this clan rose to become the most powerful warriors in all of Japan.

A prominent member of the Seiwa Genji was Yoshimitsu Minamoto (1045-1127). He was extremely skilled in the sword, the spear, and the bow and further developed his secret family art, the Genji-no Heiho, by studying spiders trapping their prey and by dissecting the bodies of dead enemy soldiers so as to carefully analyze their anatomical structure. From these observations, Yoshimitsu was able to further refine joint locks and pressure point strikes and thereby enhance the system that had been passed down to him.59 He named the resulting style of unarmed combat after the mansion in which he lived as a child, Daito. Hence arose what became known as Daito-ryu Jujutsu.60

Yoshimitsu's second son lived in Takeda in the old Kai Province, and he eventually became tied to that name. "Subsequently, the techniques of Daito-ryu were passed on to successive generations as the secret art of the Takeda house, and were made known only to members and retainers of the family."61 In the late 1500's, the Takeda Family relocated to Aizu; and the art was taught to the Aizu samurai clan, thus giving rise to the Aizu-Takeda branch of the family. In 1644, an adopted son of the family was appointed governor of Aizu, and he reformed the Daito-ryu to more effectively accommodate peacekeeping needs within the castle fortifications. He initiated a system referred to as oshikiuchi, in-close self-defense principles to be taught to senior councilors, shogunal retainers, and certain castle workers." This particular governor also mastered a school of swordsmanship that likewise influenced the Daito-ryu, and it's principles, along with the oshikiuchi were passed down to succeeding rulers of the Takeda House in Aizu.62

Sokaku Takeda (1859-1943) was born in Aizu, the seccond son of Sokichi Takeda who taught him Daito-ryu, the use of the sword and the bo, and sumo from his youth. As a young man, he traveled all over Japan, perfecting his martial arts skills and mastering the use of the sword, the bo, and the jo. He also toured the Kyushu and Okinawa islands, seeking out karate masters for knowledge and with whom he could test and refine his skills.63 Throughout these years, he maintained close contact with chiefs of Aizu-Takeda clan and received personal instruction in the oshikiuchi principles of Daito-ryu. It is said that "Takeda perfected seemingly miraculous skills of understanding another's mind and thought, and grasped the true depths of oshikiuchi."64

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Sokakau Takeda began to do what had never been done before in the long history of Daito-ryu: he began teaching the art outside the household. In his mind, he believed spreading the art throughout Japan was the best way to ensure preservation of the family's martial traditions.65 "During his lifetime, he taught as many as thirty thousand people, with their signatures preserved today in his enrollment books."66 Takeda was only five feet tall, but it is said that his techniques were "of a phenomenal level."67 Sokaku Takeda is considered one of the greatest martial artists of the modern era, and two of his most renowned students outside the family clan were Takuma Hisa (cited above) and Morihei Ueshiba. He died in 1943, during the height of World War II, at the age of 83.

morihei ueshiba

kenji tomiki

jack mumpower, jr.

tomiki aikido in north carolina

-

Any minor discrepancies in detail that may be found between this history presentation and the above-linked thesis are a result of further research conducted subsequent to the submission of this work in San Pedro, California in April of 2015. The author is making every effort to go back and revise the original thesis to match what is promulgated in this online chronicle. At such time that said revision is completed, an updated print version will be linked above ↩

-

Manchuria is a geographical and historical region in modern-day Northeast China that is bordered by Outer & Inner Mongolia to the west, Russia to the north and east, and the Korean Peninsula to the southeast. Historically, Manchuria also been referred to as Guandong which literally translates "east of the pass", a reference to Shanhai Pass in Qinhuangdao in today's Hebei province, at the eastern end of the Great Wall of China. ↩

-

Robert McLain, Grandmaster Yoon Byung-In (http://www.kimsookarate.com / intro / yoon / Byung_In_YoonrevMay3.pdf), 1. ↩

-

Chinese Chuan-fa, particularly the northern system, was the first eclectic martial art. ↩

-

At the time, most Chuan-fa instructors in that area were Mongolians. ↩

-

Karen Hoffman, Byung In Yoon: Another Story (http://www.kimsookarate.com / contributions / yoonstory.html), 1. ↩

Kim Pyung Soo was one of Nam Suk Lee’s original students who also learned from Byung-in Yoon. In 1968, he immigrated to Houston, TX where he continued to teach an art that sought to closely preserve the forms and techniques from indigenous Chang Moo Kwan, apart from the international sporting elements that have come to characterize Taekwondo. It was Mr. Soo who would later visit Byung-in Yoon’s family in South Korea and learn about his fate during and after the Korean War. ↩

Hoffman, 1. ↩

Kim Pyung Soo, Personal Interview with Byung-in Yoon’s Family (December 18, 2005). ↩

Ibid. ↩

McLain, Grandmaster Yoon Byung-In, 2. ↩

Anko Itosu (1831-1915) is often referred to as the “Father of Modern Karate.” He was the primary protege of the great Sokon Matsumura and was the first to introduce the Shuri-te tradition to Okinawan schools as early as 1901. In October of 1908, Itosu wrote a letter to draw the attention of the Japanese Ministries of Education and War to the value of teaching martial arts in the public schools. Not only was this letter very influential in the spread of karate, but it communicated a spirit of martial arts eclecticism, acknowledging value in both Shorin-ryu (i.e. Shuri-te), Itosu’s own tradition, and Shorei-ryu (i.e. Naha-te). Also, this letter’s opening statement is clear historical proof from an original source that karate is not Buddhist, neither was it tied in its historical development to manmade religion. From this letter are derived what have become known as Itosu’s Ten Precepts of Karate. ↩

Some believe that Toyama actually outranked Funakoshi because there is no record of the latter ever bearing the title shihandai. ↩

Hoffman, 1. ↩

McLain, Grandmaster Yoon Byung-In, 2. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Kushanku is also known as Kanku-dai. ↩

McLain, Grandmaster Yoon Byung-In, 3. ↩

Darrell Cook, World Chang Moo Kwan, Where Do We Really Come From? (http://www.changmookwan.net / changmookwanhistory / historyofchangmookwan.html), 13. ↩

McLain, Master Yoon Byung-In’s Legacy, 1. ↩

McLain, Master Yoon Byung-In’s Legacy, 3. ↩

Ibid. ↩

McLain, Grandmaster Yoon Byung-In, 3-4. ↩

James & Sandra Dussault, “Grandmaster Nam Suk Lee: Patriarch of the Chang Moo Kwan Part 1,” Inside Tae Kwon Do (October, 1993), 48. ↩

Cook, 13. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Jon Wiedenmen, Personal Interview with Nam Suk Lee (2000) ↩

Cook, 13. ↩

Ibid. See also John Corcoran & Emil Farkas, The Original Martial Arts Encyclopedia, New & Revised Edition (West Hollywood, CA: Trans-Euro Film Trust, 2011), 128. ↩

Dussault, 48. ↩

Ibid., 49. ↩

McLain, Master Yoon Byung-In’s Legacy, 4. ↩

The Kangduk Won was founded following a disagreement between Nam Suk Lee and Kim Soon Bae with Hong Jung Pyo and Park Chul Hee. This happened sometime in 1956 when Lee was promoted to 4th Dan in Chang Moo Kwan and Park to the rank of Sandan. It’s unclear what this disagreement was about, but it unquestionably led to Hong and Park separating from the Chang Moo Kwan and opening up their own school in a nearby neighborhood of Seoul (Cook, 13-14). All of these men were connected to Byung-in Yoon, and both of these dojos “shared the same lineage and curriculum” (McLain, Master Yoon Byung-In’s Legacy, 4). ↩

Ibid. ↩

Robert McLain (Master Yoon Byung-In’s Legacy, 4) lists in chart form a number of katas that have come down from Kim Pyung Soo. The Chuan-fa side of the chart lists several forms already mentioned earlier in this thesis. On the Shudokan Karate (i.e. Kanken Toyama) side of the chart, the list interestingly includes “Kibon Hyung 1-3,” “Pyung Ahn 1-5,” “Chulki Hyung 1-3” and “Kong Sang Kun.” Nomenclature suggests that these are related in some way to at least ten of The Twelve taught or acknowledged by Lee in San Pedro, therefore supporting the author’s conviction that these forms represent indigenous Chang Moo Kwan. ↩

McLain, Grandmaster Yoon Byung-In, 4. ↩

http://www.kimsookarate.com / gallery-present / 06_Yoon / 06_Yoon.htm ↩

The Green Book: On the Occasion of the 30th Anniversary of Founding (Sep. 1. 1946~Sep. 1. 1976) (Taekwondo Changmookwan, 1976), 16. ↩

George Fullerton, “Passing the Torch,” Tae Kwon Do Times (January, 2002), 50. ↩

Dobok is the Korean term for martial arts uniform (ghi is the Japanese term). ↩

Some old photos from the Salisbury dojo can be seen here: http://clementskaratedojo.com/lineage.html. Note the style patches, the free fighting without gear, and the absence of any tournament trophies. ↩

http://clementskaratedojo.com/index.html (emphasis mine). I cannot read this mission statement without thinking of Byung-in Yoon and Nam Suk Lee training in Seoul in 1946. ↩

James Clements trained with many renowned martial arts masters over the years and founded the National Kamibushihinkai Organization in 1981. As far as I know, he still runs the Clements Karate Dojo near Claremont, North Carolina. His website has some interesting old photos of Chun Duk Ki (http://clementskaratedojo.com/lineage.html). ↩

At http://clementskaratedojo.com/lineage.html, one of the old photos of Master Ki is captioned “Chung Duk Ki Early 1970’s” and shows him teaching in a school with a Korean and a Canadian flag on the wall. ↩

The Green Book: On the Occasion of the 30th Anniversary of Founding (Sep. 1. 1946~Sep. 1. 1976) (Taekwondo Changmookwan, 1976), 182. ↩

“Dogwood Festival Program,” Statesville Record & Landmark (Statesville, NC: April 14, 1969), Microfiche, 10 {emphasis mine}. ↩

James Clements, founder of the National Kamibushihinkai Organization, eventually earned a Sandan rank under Chun Duk Ki. ↩

These four individuals were Gary Godbey (June 1, 1974), Jerry Cope (September 26, 1974), Keith Allen (September, 1975), and Lee Presnell (September, 1975). ↩

An ad from the Lexington Dispatch dated January 15, 1980 and entitled “Self Defense Courses Offered” reads: “Instructor Richard Yount from Salisbury . . . holds a third degree black belt in karate from the Southern Karate Association” {“Self Defense Courses Offered,” Lexington Dispatch (Lexington, NC: Jan 15, 1980), Microfiche, 3}. Apparently Yount, one of Chun Duk Ki’s black belts, was still teaching as late as 1980, but there is no indication from this article that the SKA was still in existence. ↩

This style designation stood for Carolina Unarmed Combative Defense Organization. ↩

Tomiki Aikido was originally brought to North Carolina by Jack Mumpower. Mumpower was a student of Kenji Tomiki and Hideo Obha at Fu Chu Air Station in Japan. He relocated to Charlotte, NC and began teaching there in 1959, opening the first indigenoous Tomiki Aikido dojo in North America. All Aikido taught in North Carolina at this time was necessarily connected to Mr. Mumpower, so the Carolina Karate Association, by default, bore direct descent, not only with Byung-in Yoon, Nam Suk Lee, and indigenous Chang Moo Kwan, but also with indigenous Tomiki Aikido brought to North Carolina by an American student of the Japanese founders. Jack Mumpower, as of 2017, continues to teach idigenous Aikido as he learned it from Tomiki himself, and Sensei Jesse Boyd continues to train as one of his last formal students. ↩

It’s interesting to recall that the very first Chang Moo Kwan dojo was likewise opened in a YMCA. ↩

Louis Frederic, Japan Encyclopedia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 237. ↩

The Seiwa Ganji was that branch of the Minamoto clan descended directly from Emperior Seiwa Fujiwara. Minamoto was a surname bestowed by Japanese Emperors upon members of the imperial family demoted to the rank of nobility. The "demotion" from royalty to nobility was done to alleviate some of the financial burden bestowed upon the imperial household by emperors who had as many as 40-50 children. The term minamoto (i.e. origin) was chosen to signify that this new clan shared the same origins as the royal family. Specific Minamoto hereditary lines coming from different emperors developed into specific clans referred to by the emperor's name followed by Genji (e.g. Seiwa Genji). For more information, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_clan ↩

Takuma Hisa, "Daito-Ryu Aiki Budo," Shin Budo Magazine [November, 1942 (republished Summer, 1990)], 85. ↩

Neil Saunders, Aikido: The Tomiki Way (Victoria, Canada: Trafford Publishing, 2003), 6. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu Headquarters, "History of Daito-ryu: Prior to the 19th Century," Retrieved 2007-07-18: https://web.archive.org/web/20070706040728/http://www.daito-ryu.org/history1_eng.html ↩

This mirrors the testimony of Byung-in Yoon on the Chang Moo Kwan side of or heritage who did the same with Kanken Toyama, a student of the renowned karate master Anko Itosu. ↩

Saunders, 7. ↩

Hisa, 85. ↩

Saunders, 7. ↩

Ibid. ↩